Big Ice

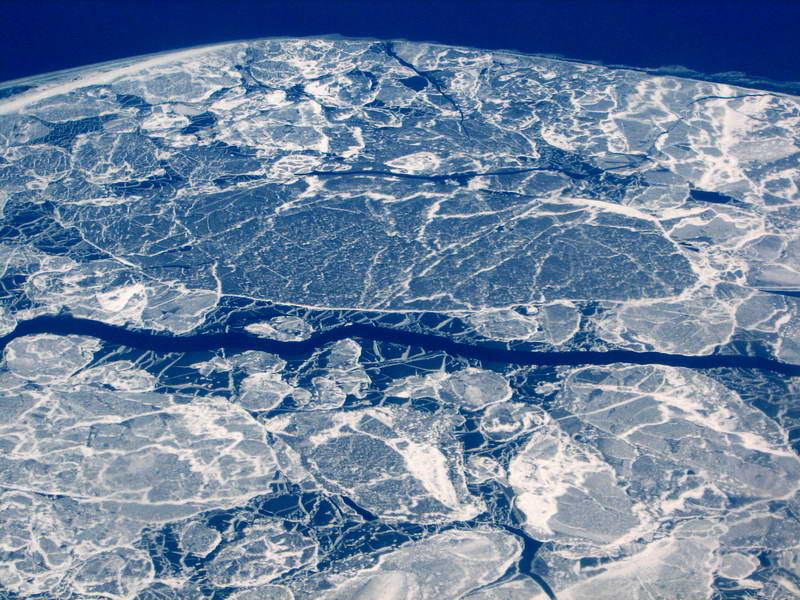

Ice on the south side of Lake Eire looking north from 30,000 ft-estimated scale: picture 5 miles wide. Wind from left to right.

Ice on the south side of Lake Eire looking north from 30,000 ft-estimated scale: picture 5 miles wide. Wind from left to right.

Summary: For ice on lakes bigger than a few miles wind and currents start to have a big impact. Ice sheets tend to be much more complex and have several types hazards not often seen on smaller bodies of water and the number of hazards per mile of travel tends to be higher. If you go out on big ice it is especially important to be an group that is experienced with big ice and to be well equiped to take care of yourselves.

Detail:

In addition to pushing the sheets around more, wind also makes bigger waves in any open water. Larger size also means the lake turn over process is likely to be at different stages in different parts of the lake. Shallow, more enclosed bays come in first and larger or deeper places later. All these factors mean it is common to have large areas of open water in big lakes.

In general, big ice is usually more of a mess than ice on smaller lakes. As you can see from the above picture, at this large scale the ice is a hodgepoge of older plates, new ice between the older ice, leads, and big bands of accumulated wind blown ice pieces.

- Fields and bands of jumbled ice are common and the degree of disruption is often higher than on smaller lakes.

- Holes (open and recently frozen) associated with disrupted ice are more common.

- Random ice sharks (blocks sticking up) can be expected. They can be hard to spot in time from a speeding iceboat or snowmobile.

- Ice piles and thick ice finger rafting occur.

- Leads are common, especially in new black ice or thawed ice sheets.

- Wide wet cracks (open or skinned over) are common as well. Sometimes these are hard to spot, especially if there is a little snow on the ice.

- Large pieces of the ice sheet blow out into open water (sometimes with fishermen or sailors on them).

- Large open areas known as polynyas are common. At ice level, large open areas are hard to see from more than half a mile away.

- Pressure ridges occur roughly every mile or so. They are often bigger than on smaller lakes.

- If something goes wrong you are more likely to be far from shore.

- New black ice can sometimes form over a huge area. It is especially vulnerable to being broken up by wind.

- Some big lakes have shipping traffic which adds another set of problems.

Big ice warrants an extra degree of caution and experience. Go slowly and use your test pole a lot. Be well prepared to rescue yourself and others. Either wear cold water protection or bring dry clothes in a water proof bag. Big ice can be great fun to explore but it is inherently higher risk and needs to be approached accordingly.

The east end of Lake Eire. The wide, smooth white band along the ice edge is about 3/4 mile of accumulated wind blown ice pieces. The picture is about 5 mi across.

The east end of Lake Eire. The wide, smooth white band along the ice edge is about 3/4 mile of accumulated wind blown ice pieces. The picture is about 5 mi across.

Leads

A number of years ago, the widest part of Lake Champlain had four inches of great, new, black ice. Several of us went exploring in our iceboats. The wind was about 5 mph, enough to move along at about 15 mph. It had just started to snow lightly leaving a thin cover on the ice. We were a couple miles off shore when the person in the lead boat, saw a slight line in the snow and stopped abruptly, within a few feet of the line. It was a recently re-frozen lead about 50 feet wide that had half an inch of ice! This was a disaster narrowly avoided. Only one person in the group had a wet suit on. Clothing that provides cold water protection is an especially good idea on big ice since there are lots of new ways to get very cold and wet, far from home.

Leads off Burlington on Lake Champlain, spring conditions.

Leads off Burlington on Lake Champlain, spring conditions.

Ice sheets pull apart on larger bodies of water leaving wide cracks (leads) that range from a few feet to hundreds or thousands of feet wide. Once they are more than a foot wide they can't be crossed by a vehicle and most people would be hard pressed to jump across more than two or three feet. Once they start to seporate they often open to more than three feet in well under a minute. Leads are typically long and straight with abrupt zags here and there. They are different from melted pressure ridges in that the ice breaks and moves apart as opposed to melting in place. They are very common on the Great Lakes. Leads typically form when there is some open water for the ice to move to. They form most easily when the ice is less than a few inches thick or when it is well thawed and especially weak in tension. They are an indicator that the sheets may be able to break off and get blown out into open water. If you encounter a lead, you should seriously consider returning to shore or at least to ice with a lower likelihood of breaking between you and shore. If you have to cross one, there may be places where the crack is near perpendicular to the ‘pull-apart’ direction. It may be narrow enough to cross there. There is a good chance that ice on the open water side of a lead is moving in some direction. If it is windy it is probably moving relatively quickly so your escape options are likely to change soon, probably for the worse.

Two pieces of ice that have drifted off the SE shore of Lake St Clare in light winds. Scale: The big piece is roughly 3/4 mile long. The 'ice' in this case seems to be accumulated windblown ice pieces.

Two pieces of ice that have drifted off the SE shore of Lake St Clare in light winds. Scale: The big piece is roughly 3/4 mile long. The 'ice' in this case seems to be accumulated windblown ice pieces.

Breakaway Ice Sheets

It seems like every year or so there is a news story about a sheet of ice getting blown out into open water with a bunch of fishermen on board (often with vehicles and shanties). This is one ice event that gets close to a 'shark attack' level of press coverage. Typically this happens on big ice with a strong wind blowing toward open water. The sheet typically separates at existing lines of weakness (pressure ridges, tectonic cracks, etc). The passage of an icebreaker (ship, barge, or ferry) can cut a sheet loose. The following are a few stories.

Lake Champlain:

It had been warm for a couple days and the ice was a foot or more thick at the southern end of the widest part of the lake. The center of the lake was open a couple of miles north. People had been fishing on the ice for weeks. The wind was from the south with gusts into the 40’s. The ice parted with a loud bang at a 'crack' (probably either a pressure ridge or tectonic crack) and a big sheet was blown into the open water with several fishermen aboard. People on shore notified the police. The fishermen described the sheet as getting smaller as wind and ever bigger waves broke and removed pieces from the edges. A difficult, high wind, helicopter rescue saved the day.

Lake Michigan, Saginaw Bay:

The bay had ice but the main part of the lake was open. The wind was blowing toward the main lake. An iceboat regatta was being sailed on the bay. Some of the boaters noticed a crack was starting to separate the plate they were sailing on from ice attached to shore. They acted quickly and were able to get everyone across the crack as the sheet rubbed along the shore fast ice.

Lake Champlain:

Monroe Allan, one of our stalwart local sailors in the 70’s and 80’s once found himself on a small loose plate and was able to sail it sideways enough to get it to brush against landfast ice and make his escape.

Lakes Eire and St Clair:

Lake Eire is shallow enough to freeze at least partially most years. It is definitely big ice. It has a reputation for stranding fishermen on detached ice flows. Lake St Clair is considerably smaller but still big ice. The following links are to news accounts for a couple of breakaway events.

Lake Eire Link Lake St Clair Link

The overall message is: consider all these possibilities and other ones not described here when traveling on big ice. An obvious warning sign is moderate to high winds, especially when blowing away from or along shore. It takes very little wind to move an ice sheet if it is not well 'locked in'. Warm weather, thawed ice, shipping traffic, currents and other factors can be important as well.

Account of a Blizzard on Lake of the Woods, 20 miles from shore